Globally, New Zealand has seen one of the highest house price increases in recent years, as well as one of the highest population growth rates and one of the steepest declines. mortgage interest rates.

These are some of the findings of research undertaken by the Reserve Bank (RBNZ) to better understand the sustainability of house prices in New Zealand. Paul Conway, RBNZ Chief Economist gave a speech on Thursday which summarizes some of the research.

In an article titled: How to stack? The New Zealand property market in the international contextRBNZ’s Hamish Fitchett and Punnoose Jacob compared the New Zealand property market to that of 12 other developed countries between 1991 and 2021.

They say that until the global financial crisis of 2008, house price growth in New Zealand was broadly in line with most other countries; but the model changed after the GFC.

“Real house prices in New Zealand flattened for a few years after the GFC, before experiencing a rapid escalation.

“The rise in house prices in New Zealand since 2008 has exceeded that of all the other economies in our sample,” the report’s authors state.

“New Zealand’s soaring property prices have also pushed New Zealand to the higher end of the cross-country spectrum when it comes to two other key housing market indicators; the price-to-rent ratio and the price ratio. /price. income ratio.”

The authors note that demand for housing strengthens as the population grows and mortgage interest rates decline.

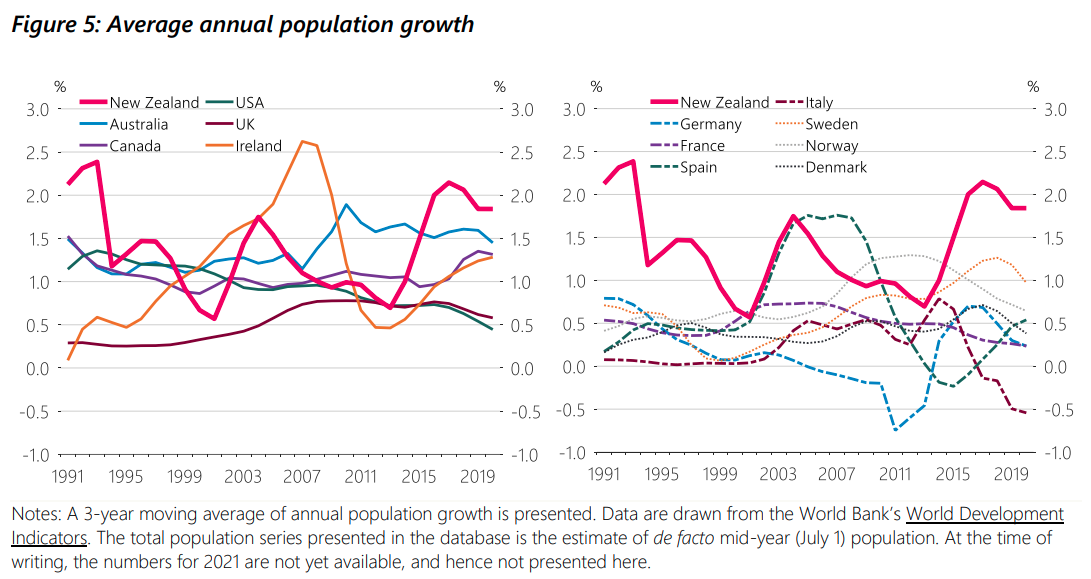

“Figure 5 examines the population growth rates of our sample. New Zealand has been at the high end of the range for most of the past three decades in terms of population growth. Although at From low levels by global standards, New Zealand’s population, supported by high immigration, has grown rapidly,” they say.

Fitchett and Jacob say that although net immigration fell immediately after the GFC, it started to increase after 2011 and continued to strengthen until early 2016 and remained at high levels.

“Population growth in other economies has been relatively weaker, and even negative in Germany, France and Italy in several episodes over the past 15 years.”

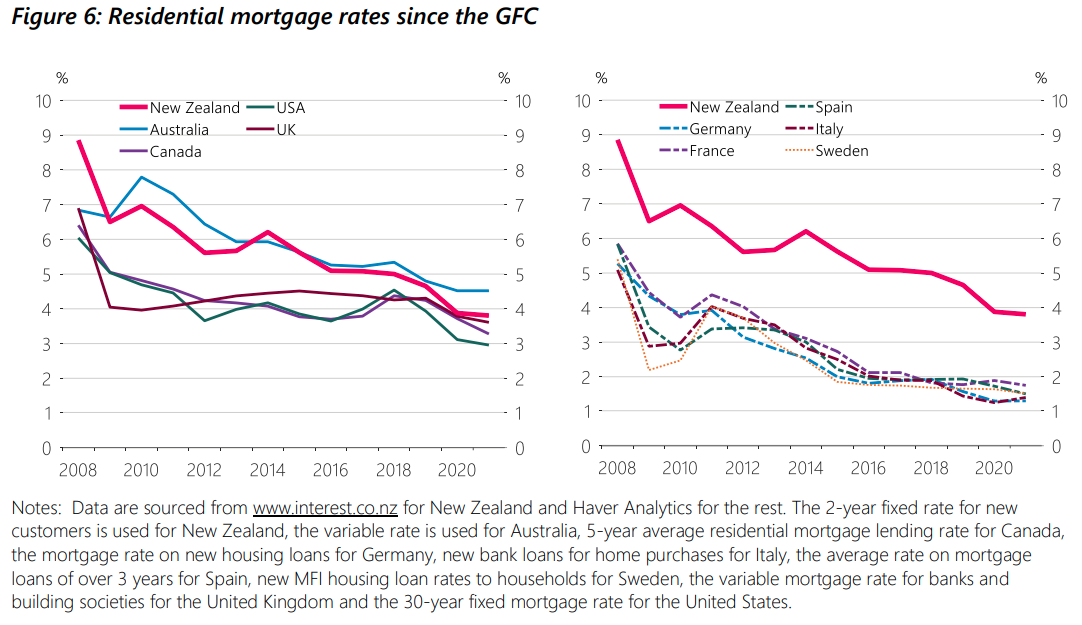

Regarding mortgage rates, the authors argue that it is difficult to compare rates between countries because the types of relevant mortgage contracts vary between economies and perhaps also over time.

“With this caveat in mind, Figure 6 illustrates the continued decline in selected mortgage rates for most economies in our sample, after the GFC.

“The New Zealand mortgage rate started at a higher level than other economies in 2008.

“Between mid-2008 and mid-2009, the [Reserve] The Bank relaxed the official exchange rate by 575 basis points.

“This in turn reduced the cost of mortgage debt interest rates to historically low levels at the time. After rising slightly until around 2014, the mortgage rate has steadily declined.

“In 2021, the New Zealand rate seems to have fallen the most in our sample; around 500 basis points.”

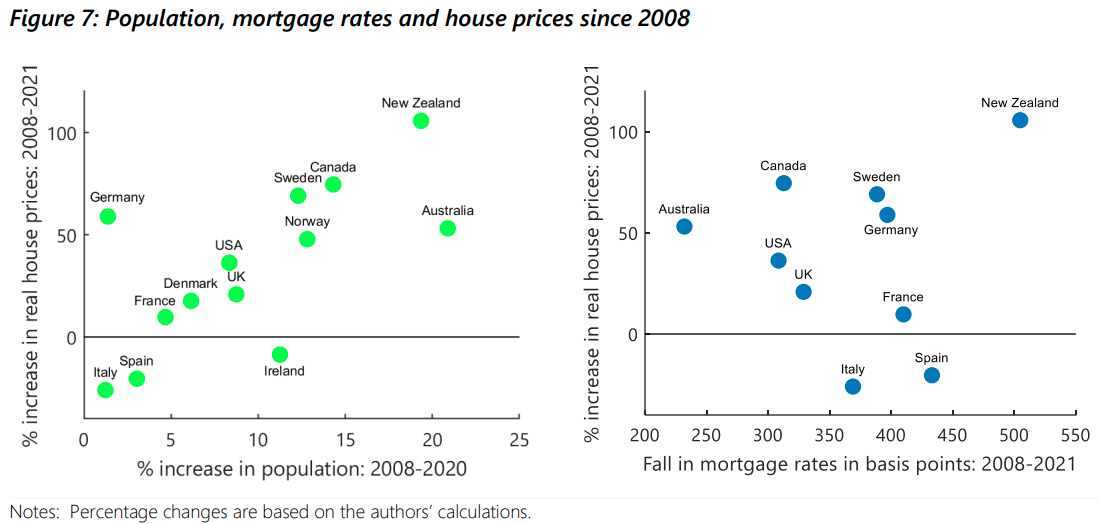

The authors then present “Figure 7”, which presents scatterplots comparing the changes in population (left panel) and mortgage rates (right panel) since 2008 to changes in real house prices over the past year. the same period.

“Two key messages emerge from the figure,” the report’s authors state.

“First, it suggests that post-GFC house price increases are more strongly correlated with population growth in all countries, while the corresponding correlation with falling mortgage rates is weaker.

“Secondly, not only has New Zealand seen the largest increase in house prices since the GFC, but it has also been accompanied by the largest increase in population and the largest decline in mortgage rates in the economies. of our sample.

Fitchett and Jacob say residential construction in New Zealand grew at a rapid pace after the global financial crisis, in fact faster than in most other economies.

“However, New Zealand’s population has also grown at an increasing rate, again near the highest in our sample.

“This mismatch limited housing availability; the number of available housing units per capita steadily declined over most of the 2010-2020 period, and was the lowest of any economy we consider.”

The authors claim that the relatively low supply of housing in New Zealand has been accompanied by high construction cost inflation by international standards.

“On the other hand, demand from the New Zealand property market has been boosted by robust population growth and mortgage rates which have seen the largest post-GFC decline among the economies we considered.”

The lower interest rate cost of mortgage debt along with robust population growth likely supported an increase in demand for homes. The combination of high demand and limited supply has generated an escalation in house prices in New Zealand, more than in other economies, Fitchett and Jacob say.

“To sum up, the combination of relatively stronger factors on the demand side and relatively weak factors on the supply side has pushed house price inflation in New Zealand towards the upper end of the cross-country spectrum. .”

*This article was first published in our email for paying subscribers. See here for more details and how to subscribe.