The view from the Sierra Nevada foothills in Southern California can be stunning – pine forests and chaparral spread across an often rugged landscape. But as more people build homes in this region, where development is entering wild land, they face some of the highest wildfire risks in the country.

The type of trees, plants, and grasses in any location will influence the likelihood of the area burning. However, our new research shows that some areas of the interface between nature and the city – the land where development ends and wilderness begins – are at much greater risk of burning than others. One of the main reasons is the vulnerability of local vegetation to drying out in a warming climate.

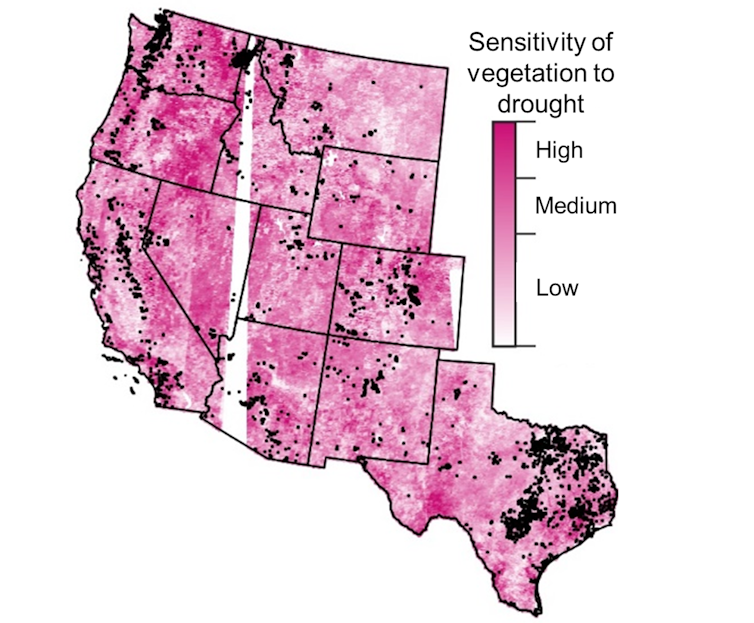

In a study published February 7, 2022, our team of climatologists, fire scientists, and eco-hydrologists mapped where vegetation creates the highest fire risk in the western United States. We then compared this map to where people moved in the area. in the interface between nature and the urban.

We were surprised to find that by far the fastest population growth rate is in areas with the highest fire risk. This includes multiple regions in California, Oregon, Washington, and Texas.

Plant susceptibility has a big effect on fires

When a fire breaks out, the area that burns increases significantly if an area’s vegetation is drought-sensitive, meaning it dries out easily after periods of low rainfall and high temperatures.

Krishna RaoCC BY-ND

Just as a succulent survives a water shortage better than, say, a lemon tree, some plants lose moisture faster in dry conditions. Such diverse sensitivity can have a significant effect on wildfires. In fact, we found that for the same increase in drought conditions, the area burned increases twice as much in the most sensitive regions as in the least sensitive regions. As a result, the fire danger in areas like southern California, eastern Oregon and central Arizona was well above average. But what about human exposure to wildfires?

The demographic boom of the interface between nature and the urban

We found that while the number of people living in the interface between nature and urban areas globally doubled from 1990 to 2010, the population in its most at-risk regions increased by 160%. As more people move into these areas, the possibility of fires starting increases, as does the number of people at risk.

In total, the population of these high-risk areas increased from 1 million in 1990 to 2.6 million in 2010, the last year for which detailed demographic data is available. This is an increase equivalent to the current populations of San Francisco and Seattle combined.

More people still live in low-risk regions of the nature-city interface, where the population grew by 107% from 5 million in 1990 to 10.4 million in 2010, but high-risk regions risk have grown much faster.

We do not know what is causing the population boom in these very sensitive areas of the western United States. Building codes, wood-dependent communities, and people seeking homes surrounded by forests may have contributed to the expanding interface between nature and cities, but these factors alone do not explain why the population would increase the most in the most vulnerable regions.

However, a map of vegetation sensitivity to water shortages can provide some insight. By linking satellite estimates of vegetation dryness to climate observations, we have created continental-scale maps of vegetation moisture. For the first time, we now know the precise locations of the vegetation most vulnerable to drought and therefore prone to fire.

The map shows that the Sierra Nevada foothills in Southern California, the San Francisco Bay Area periphery, San Diego and San Antonio all have drought-sensitive vegetation and have seen their populations expand to the interface between nature and cities.

Krishna RaoCC BY-ND

Further studies examining demographics and local land use and development regulations in these regions can shed light on the drivers of growth in these high-risk areas. In the Bay Area, for example, the lack of affordable housing has pushed people further from cities and could encourage more development in the interface between nature and urban areas, including high-risk areas that had no not been developed before.

What can people living in risk areas do?

The disproportionate population growth in high-risk areas is a warning that the likelihood of humans starting a fire in an area with high-risk vegetation is increasing – and may be higher than previously thought.

Community leaders can use this knowledge to identify where human activity overlaps with drought-prone regions to improve local land-use planning, prepare firefighting resources, and develop pathways. safer evacuation.

Homeowners can maintain a safe defensive space of at least 100 feet of unvegetated land on all sides of a home to help protect their structures in the event of a wildfire. Renovating homes using fireproof materials or double-glazed windows can also help.

[Over 140,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Preventive measures like these can limit ballooning losses from wildfires, including the devastating air quality from wildfire smoke, while allowing humans to coexist more safely with people. natural fires.

Preparing homes for wildfires can take months, so it’s important to use the winter, when many of these areas have their wet seasons, to be ready when the land dries up and the fires of forest intensify in the spring.