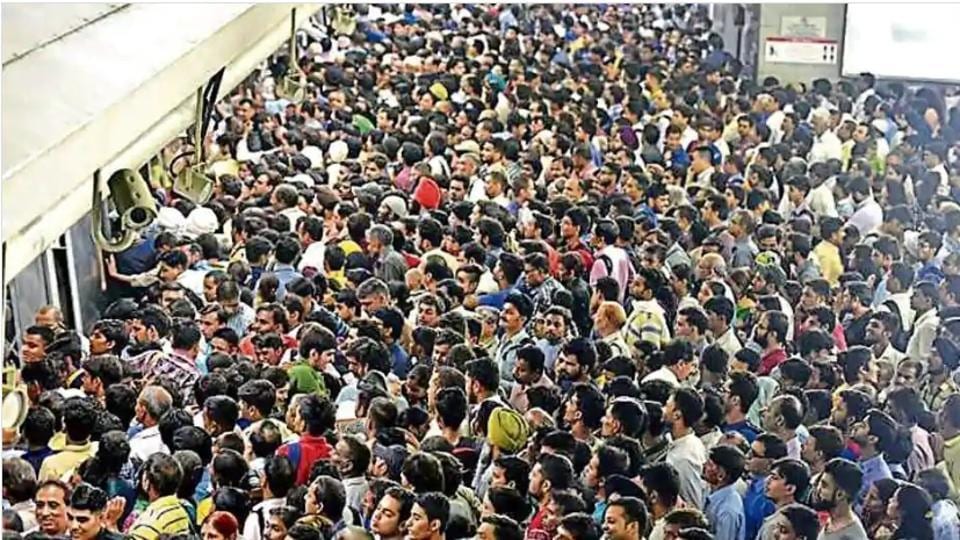

There are growing calls for a national population control law. A public campaign, which began on Republic Day, to demand legislation to control the country’s population has won celebrity endorsements and the support of thousands of social media users. A deputy (MP) has drafted a law which proposes to limit the number of children per couple to two.

According to the bill, people who wish to have more than two children will need to obtain permission from a district council which will include a senior government doctor, the district collector and representatives of local urban and rural administrative bodies. The district council will decide if there are medical reasons — the reasons are not explained in the draft — which oblige the applicant to have a third child. Other sections of the bill require the government to “encourage, promote and motivate married couples” to opt for small families. Citizens who break the law will not be able to receive any benefits under government-sponsored welfare schemes. The bill says that rapid population growth is creating pressure on natural resources. There are other MPs who think the country needs a population control law. A Union minister said the country’s effort to enact the law was being derailed by opponents who claimed it was a covert attempt to control the rapid population growth of a religious minority.

The provisions of the bill resemble those of China’s one-child policy that would have prevented hundreds of millions of births. China, which now faces the prospect of a steep population decline, has withdrawn the policy, but the Chinese, who are now more prosperous, urban and educated than they were in 1979 when the law was introduced , want no more children. China’s population is expected to start declining after 2029.

India has never used coercive means to control its population growth, except for a brief period in the 1970s, but local government and cooperative housing laws contain clauses that prevent people with more than two children to stand for election to these organizations.

The question is, does India need a population control law? Most parts of the country are experiencing a decline in population growth. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 4, conducted for 2015-16, shows that the fertility rate – the number of children per woman – is below 2.1, which is called replacement level, where two children replace their parents (the 0.1 represents mortality). Nearly 60% of the country’s population lives in states where the fertility rate, that is, the number of children per woman, has fallen below two.

For example, Maharashtra, which has a tenth of the country’s population, is experiencing a rapid decline in population growth. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS) found a drop in the number of children in elementary schools, indicating that people are having fewer children. The NFHS 4 for 2015-16 indicates that the number of children under 15 as a percentage of the total population of Maharashtra fell to 24.5% in 2015-16 from 30.6% in 2005-2006 when the NFHS 3 was compiled. The fertility rate—the number of children born to a woman—increased from 2.1 to 1.9 between the two survey periods. So Maharashtra may not need the law.

NHFS surveys over the past few decades indicate that women’s level of education is a major factor in the number of children they decide to have. For example, in Bihar, when the percentage of literate women rose from 37% of the population in 2005-06 to 49% in 2015-16, the fertility rate rose from 4 to 3.4. In Uttar Pradesh, where the female literacy rate rose from 44.9% to 61% over the period, fertility rates fell more sharply — from 3.8 to 2.7. A higher literacy rate means fewer children. In Goa, where the female literacy rate was 89% in 2015-2016, the fertility rate was 1.7. In Kerala, the female literacy rate was 97% and fertility was 1.6.

Better law enforcement, which requires the government to guarantee free and compulsory school education, will help states where fertility is still above replacement rates to make the transition to low population growth.