Illness slowly took away Noemi Fleming’s elderly mother, the first clues in anecdotes or repeated phrases. Then lost keys and bills. Then, Fleming caught his mother walking outside in the middle of the night, looking for the diary.

“Mom, it’s 1 a.m.,” Fleming would tell her. “The newspaper doesn’t arrive until 8 p.m..”

On HoustonChronicle.com: Alzheimer’s diagnoses are increasing in Harris County. This tour aims to raise awareness among caregivers and the public.

Fleming’s mother died at 91 in their hometown of Rio Grande City after a two-decade battle with Alzheimer’s disease, a brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills. The family’s story is familiar in Starr County, a mostly rural and heavily Hispanic county of about 65,000 on the Texas-Mexico border, where about 26 percent of Medicare beneficiaries have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. This rate is the second highest among all US counties, according to Medicare data.

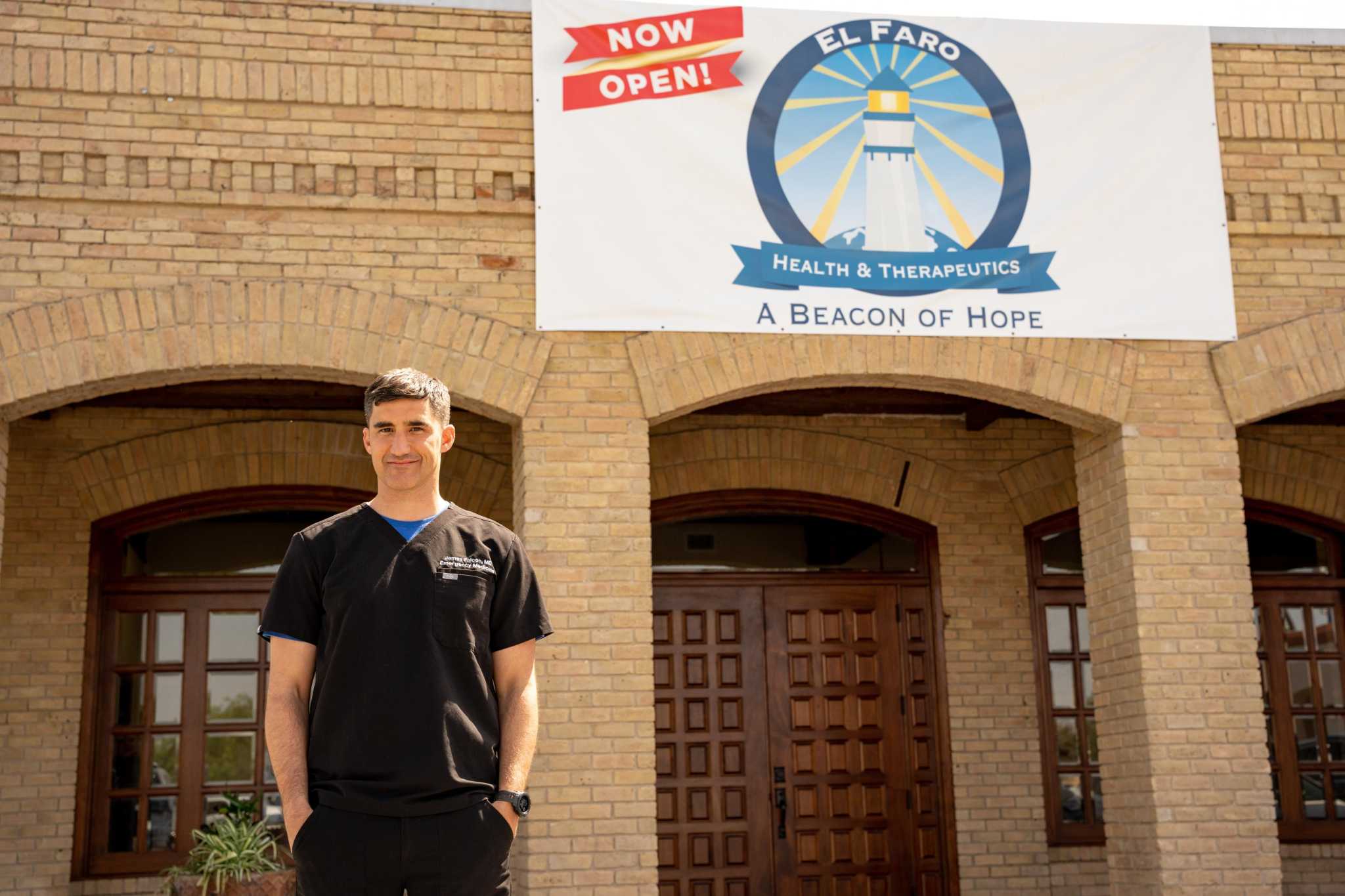

The Starr County figures underscore a recent push in the Rio Grande Valley to better understand how and why the disease disproportionately affects Hispanics, who, along with blacks, have traditionally been underrepresented in research on the disease. Alzheimers. The county’s first private clinical research site, El Faro Health & Therapeutics Center, recently opened in Rio Grande City, and federal funds were awarded last month to the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley to investigate a wide range of underlying causes.

Efforts are still in their early stages, but eventually researchers hope to identify ways to diagnose and treat the disease more effectively.

“One of the problems, because there’s no real cure, is that a lot of the attention has just been to try to prepare families for what’s to come and make sure that families have things in order,” said lead researcher Dr. James Falcon. in El Faro.

underrepresented

Fleming, 69, jumped at the chance to join the first Alzheimer’s study in El Faro.

The research would help develop inexpensive tests to detect amyloid plaques, or sticky clumps of protein that accumulate around brain cells and disrupt brain activity.

Along with seeing her mother’s decline, Fleming worked as a nurse for more than 30 years at Starr County Memorial Hospital. She saw the value of learning her diagnosis early and potentially helping others do the same. And she could easily go to the three appointments required.

“I’m glad they did it in Starr County,” Fleming said. “Because (usually) when it comes to clinical trials, you’ll probably have to go to a big city.”

On HoustonChronicle.com: New ruling clouds future of Alzheimer’s drug Houston doctor had seen promise with

Studies from the National Institutes of Health have linked underrepresentation to a lack of research efforts in minority communities. Other barriers include distrust of the predominantly white research establishment and inadequate education about the purpose of research. Studies also cite medical staff that do not represent participants’ culture and eligibility criteria that disproportionately exclude minorities.

The El Faro Clinic was created as an “antidote” to these problems, said John Dwyer, president of the Global Alzheimer’s Platform Foundation, an advocacy group that opened the clinic in partnership with James Falcon and his father, Dr Antonio. Falcon. The eldest Falcon, a longtime family doctor, grew up in Rio Grande City.

“There is an appropriate and profound effort to ensure that all clinical trials represent the population more broadly affected by the disease,” Dwyer said, pointing to a common estimate: Black people are twice as likely to be diagnosed with the disease. Alzheimer’s disease than whites, and Hispanics are 1.5 times more likely.

Dwyer said the study is still in the recruitment phase. The group aims for at least 20% of attendees to be black or Hispanic.

Current research

When Fleming enrolled in the El Faro study, she was not surprised to learn that her community was disproportionately affected by Alzheimer’s disease. She frequently saw patients with the disease in the hospital. But she always wondered why it affected some people and not others.

In El Faro, a series of tests revealed that she faced a low risk of Alzheimer’s disease. His mother’s siblings did not have Alzheimer’s disease, but Fleming remembers at least one of his mother’s parents being hospitalized with dementia – a general term for a loss of thinking skills severe enough to affect everyday life.

Further research may lead to possible answers.

A large-scale study published April 4 by the UK Dementia Research Institute found 42 genes that may serve as pathways for the development of Alzheimer’s disease, providing compelling evidence that inflammation and the immune system play a role in disease.

“Lifestyle factors such as smoking, exercise and diet influence our development of Alzheimer’s disease, and taking action to address them now is a positive way to reduce our own risk,” according to a statement from study co-author Julie Williams, director of the center at Cardiff University’s UK Dementia Research Institute. “However, 60-80% of disease risk is based on our genetics and so we must continue to search for biological causes and develop much-needed treatments for the millions of people affected around the world.”

On HoustonChronicle.com: The troubling link between veterans and Alzheimer’s disease, and what Houston experts are doing about it

Dr. Gladys Maestre, director of the Rio Grande Valley Alzheimer’s Disease Resource Center for Minority Aging Research, has several theories about the high prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in and around Starr County.

Social isolation or chronic stress from a heavy border patrol presence could contribute, she said. It could also be related to the high number of uninsured residents — about 35% in Starr County alone — coupled with the low number of nonprofit health centers, she said.

Maestre, who is also a professor of neuroscience and human genetics at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, is working to bring together 2,500 older adults with Alzheimer’s disease to participate in a $2,000 grant-funded study. $9 million from the National Institute on Aging.

She will investigate a wide range of risk factors through in-person interviews and special technologies, such as facial recognition software and memory tests using virtual reality. She begins her work in Brownsville.

“Hopefully we can learn from this and get to Zapata and Starr counties,” she said.

Treatment

For Antonio Falcon, clearer answers can’t come soon enough.

After more than four decades caring for patients in the town where he grew up, he has grown accustomed to telling Alzheimer’s patients and their families the hard truth: he had no medicine that treated the disease itself, only those who can prolong comfort and independence. . Deterioration was inevitable.

So when the Food and Drug Administration last year granted accelerated approval for Aduhelm, a monoclonal antibody designed to slow the onset of disease by targeting amyloid plaques, he was thrilled. It was the first drug approved to treat Alzheimer’s disease in 18 years, and the only one designed to treat the underlying cause.

“It’s a huge door that has opened for us,” he says. “All of a sudden we were on the forefront of getting medicine for our patients.”

Doubt quickly surrounded the drug. Questions persisted about its benefits, and some patients reported severe brain swelling or bleeding. Public health officials strongly advise limiting its use.

On HoustonChronicle.com: UTHealth administers first dose of controversial Alzheimer’s drug in Texas

The FDA is investigating its own approval of the drug. And last week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services dramatically limited Aduhelm’s coverage, ensuring Alzheimer’s patients in Starr County wouldn’t have access to the drugs, which are estimated to cost about $28. $000 for one year of treatment.

The decision was applauded by Alzheimer’s disease experts who continue to urge caution over its use. Antonio and James Falcon both remain disappointed that the agency has not opened up access to more vulnerable groups.

But they are hopeful that three new monoclonal antibody therapies are currently in clinical trials. In the immediate term, they are committed to arousing more interest in the study of El Faro.

“People are developing (dementia related to Alzheimer’s disease) as we speak, and it’s not going to stop,” Antonio Falcon said. “It’s a one-way street for them at this point.”

julian.gill@chron.com